A. D. Amorosi, July 2014

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW

If A.D. Amorosi can’t be found writing features for ICON, or the Philadelphia Inquirer or Metro, he’s probably hitting restaurants like Stephen Starr’s or running his greyhound

P.O. Box 120 • New Hope, PA 18938 • Voice 800.354.8776 • Fax 215.862.9845 • www.icondv.com • www.facebook.com/icondv

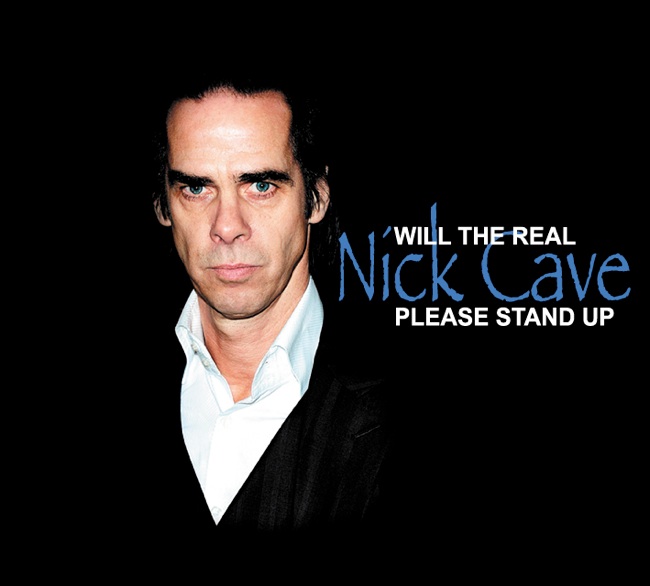

To say that Nick Cave operates on his own level apart and away from other writer-singer-performers is a minor observance of his unique stature at this point in his long career.

Though certainly not the first baritone vocalist to be obsessed by death, America, love and violence (hello David Bowie and Scott Walker) Cave has always taken such passions to their extreme, as well as lacing their allusions with a literary language and a rich well of reference unwitnessed since Leonard Cohen and Lou Reed’s initial works. Unlike those icons of poetic text, Cave—the finest artist to emerge from European post-punk—had an energy that was as bizarre as it was unbound—like a caged, wild child let loose on Proust, Joyce and Carson McCullers. The results of his labors, most often displayed through the auspices of his longtime ensemble The Bad Seeds (but not exclusively, see the stripped-down, rude, raw Grinderman) have ranged from the dark discord of early albums such as From Her to Eternity and The Firstborn Is Dead to the more pastorally displayed gloom of latter-day Cave-Seed collaborations, No More Shall We Part and the double-album Abattoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheus.

Everything changed though with last year’s Push Away the Sky an album and tour that opened Cave up not only to the sound of epiphany, but a certain ebullience in finding such joy. “Yes, joy,” says Cave pacing throughout several rooms during what was my eleventh interview with the Australian writer-singer since his days as a member of the legendarily savage The Birthday Party. “There was definitely a certain celebratory spirit to the music and lyric of Push Away the Sky as well as the tour that followed, especially in America.”

This month, Cave looks to conjure that same gleeful spirit with a show at the Mann Center (July 25) as well as a screening of the soon-to-be-released expressionist documentary on his doings, 20,000 Days on Earth at the Trocadero (July 27).

Remind him that this is very nearly our twelfth conversation and Cave teases how “nice it is that we have stayed together. I hope that I don’t repeat myself too often,” before discussing the process that’s brought him to 56 years of age, and whether he’s become the man he thought he would be growing up.

“I was always older in my thinking, I believe,” says Cave. “The people I was influenced by were older, and even perhaps the people I measured myself against—if I ever really actually did that—were older, rather than, say, my contemporaries. Now that I’m older, I expect that I’ve caught up… I don’t know.”

Having witnessed the live Cave experience since the time of The Birthday Party and its manic avant-rock ride (“you have to not take Birthday Party into consideration, as it was a different thing altogether”), his is a position where reserve meets abandon. “In terms of the Bad Seeds and I, we have mastered the art of control as well as the abandon of which you speak. I think all of us have within that band. There is a difference though, now,” Cave says with a great pause. “Our performances have become far more joyful than maybe they were ten years ago.”

There’s great energy within the Bad Seeds, part of which comes from the cinematic yet sparer sounding melodies (longtime arranger Mick Harvey left the band and took with it some of the lushness) and Cave’s unwillingness to play judge or jury in some of its more dramatic looks at good people doing lousy things. Playing an album as such nightly does a lot to change even the most seasoned road dogs. “Quite truthfully, a lot of the newfound joy with the Bad Seeds and I has to do with touring the states last year as well as our decision to keep playing. There was something about those performances of 2013 that have us given a different look at the states—a different more unique impression. Before that, we had own way of doing America. Now, it’s more communal and celebratory.”

Having witnessed Cave’s Seeds sell out the Keswick Theater in 2013 and watching the radiant love between the band and the audience, you could tell than there was epiphany to be found, even during Cave’s darkest songs.

For this, Cave blames the fact the most recent album is more ambiguous than Bad Seeds’ albums past, much more obscure, intangible and amorphous than anything they’d recorded previously. “That sort of thing allows listeners to paint their own pictures, as opposed to my previous recordings and live shows where, quite frankly, they came off as ‘Here I am world, I’m fucking Nick Cave.’” This time, listeners suddenly became closer to him, to become part of his songs. “I think that they got beyond the wall, my wall. Do you like that theory?”

Where going beyond the walls are concerned nothing would seem so immersive and invasive as a documentary. That is if it were anyone but Cave. Unlike rockumentaries with Metallica (Some Kind of Monster) where bands sit through therapy sessions or even Let It Be where you watch the Beatles disintegrate before your very eyes until they nearly jump off a roof, Cave’s 20,000 Days on Earth, directed by Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, takes an avant-garde road, with build-around set pieces through which Cave can dramatically improvise. “No, not exactly act,” says a relieved Cave, the author of such films as The Proposition. Not only does Cave get shot several times during his 20,000th day of existence, he hangs in his office, eats with Bad Seed Warren Ellis while viewing Scarface, sits through a therapy session, and drives with Kylie Minogue. Other people In the same car with the singer include Ray Winstone and Blixa Bargeld, the legendary noise guitarist who famously left the Bad Seeds with a brief email after finding himself disappointed with Cave’s musical direction at the time. “I hadn’t seen or spoken with Blixa for twenty years, so that was a surprise,” he says.

So why did Forsyth and Pollard succeed when others had tried? What pitch did they give Cave?

“It didn’t have anything to do with any sort of pitch, yet had everything to do with the fact that we got them involved in the studio when we were recording [the pair directed the video to Dig Lazarus Dig!], then commissioned them to come in and shoot footage for Push Away the Sky’s press kits, and really got on very well with the both of them. While they were around, I found them helpful to a certain visual aspect of what we were doing. We don’t really allow many people into our world, so to speak…our process… but the footage they captured was so great, we began to think about something more, something wider to put the footage they’d shot into.

After the directing duo suggested a documentary in which Cave had no interest, the notion of something fuzzily and fictitiously narrative—something unconventional—became a better idea, especially when they propositioned that Cave improvise his way through fake moments of his real life—or real moments of his fake life.

It wasn’t uncomfortable to act, as he wasn’t acting. Instead, he was an improvisational device moving through sets. “No it wasn’t uneasy being part of one’s own life. The only thing that would have made me uncomfortable would have been if I had to try to do something. That would have seemed pretend.”

Joke with Cave that it’s telling he gets shot three times in the film and he laughs before discussing the “lovely thing that runs through this film” that’s supposed to be a day in the life of Nick Cave. Rather than have some “real” psychological discourse, the trio allowed the film to be a masquerade where everything that happened during that day was fake. “None of it is real, or even close to it. My psychoanalyst isn’t real. I don’t have any grand archives. The bedroom is not my room. Those offices are not my offices, nor are the bathroom or mirror I stand in front of mine. Within those fake sets, everything was improvised, so I never really knew what they were going to get or use. It isn’t a lie. It’s just all fake, yet somehow there’s a certain truth that came through. It’s just a more interesting way of coming out with the truth that anyone thought possible at the beginning.”

The most dynamic truth comes from the car conversation between Cave and Bargeld, two intense men and friends, sharing their vision and standing their ground. Cave wasn’t surprised that there was so much honest conversational ease between them after so much time had passed. “Neither Blixa nor I have ever been interested in doing something that doesn’t have an emotional impact of some sort. There wouldn’t be any reason to do anything. It would be a complete waste of time. It’s true that we haven’t spoken to each other in years, so putting us into a car, with such close proximity, well…” Cave trails off, perhaps thinking of what could have been.

Along with touring and playing solo piano shows in tandem with 20,000 Days, Cave is currently composing new music for the Bad Seeds—“Tiny ideas, tiny strands really. Nothing I can talk about, though I can say that it will be very different from Push the Sky Away.” As for pinpointing when it will be done or when Cave might move toward his next project without Bad Seeds, Cave says that the “fires and passion and immediacy” of everything he does is harder to harness than mercury when he gets started. “I just don’t have that level of clairvoyance,” says Nick Cave. “Not yet.”

With Bad Seeds at its spirited high and a dramatized documentary screening this month, can we find the true Cave between the two poles?