Pete Croatto, Cinematters, July 2014

Life Itself

An ICON contributor since 2006, Pete Croatto also writes movie reviews for The Weekender. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Broadway.com, Grantland, Philadelphia, Publishers Weekly, and many other publications. Follow him on Twitter, @PeteCroatto.

P.O. Box 120 • New Hope, PA 18938 • Voice 800.354.8776 • Fax 215.862.9845 • www.icondv.com • www.facebook.com/icondv

I never met Roger Ebert, who died last April at age 70, but I loved him. The film critic made me see movies as flickering images of a person’s soul, not just rainy day distractions. His delicate, concise prose inspired me to become a writer, which ceased being an occupation long ago. It’s in my DNA. He brought joy and intelligence and color into my 12-year-old world, and he made me seek it from other sources.

Perhaps it’s best that a meeting never happened. Who wants to see their hero as human? That’s what you are. I want to remember Ebert walking into the sunset to begin his leave of presence.

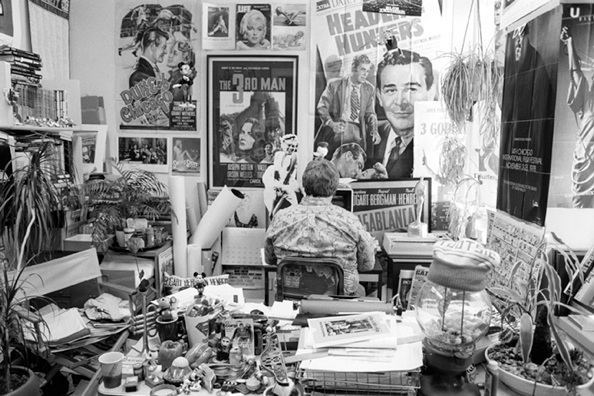

Maybe that’s why I wasn’t enthusiastic to see Life Itself, the new documentary that combines interviews, old video clips, and footage of Ebert’s wobbly final months battling various ailments. So I proceeded carefully. Director Steve James (Hoop Dreams) does a marvelous job constructing the parts of Ebert’s life that were underdeveloped in his gorgeous memoir—particularly his combative relationship with the late Gene Siskel, his TV partner—through interviews with friends, colleagues, and family members.

Forget formality. Life Itself is like a well-thumbed, yellowing photo album. In the film’s opening moments we see black and white photos of a young Roger accompanied by a brassy, tuba-fueled score. Interview subjects are captured in bars, offices, and homes. There’s a warm, familial quality to James’s approach, which makes sense since Ebert was a father figure in contemporary film. We’re basically hearing all the great, untold stories about Dad. Did you know that Siskel was petrified Ebert—“He’s an asshole, but he’s my asshole”—would leave At the Movies? Or that Ben Bradlee desperately wanted Ebert to write for The Washington Post? Forever a Chicago Sun-Times loyalist, the critic kept refusing. “I’m not going to learn new streets.”

Life Itself serves as a third-person addendum to Ebert’s titular memoir, but the lasting beauty (and relief) of James’ film is how Ebert comes across as a sage in the last months of his life when he had every reason to pack it in. “I have no fear of death,” he says at one point. “We all die.” The movie’s most inspirational scene, the one I can’t shake from my mind, comes when Ebert is confined to a hospital bed. Salivary gland and thyroid cancer has long locked Ebert’s face into a grotesque smile. Speaking is impossible—except electronically. He cannot eat or drink. A nurse feeds him through a tube, an act that elicits an unholy wheezing. But it’s OK: there’s a notepad on his lap, a laptop by his side.

Writing was something Ebert was always good at. As the rehab and the days in sterile rooms mount, and James keeps the cameras rolling, movies and writing remain. They freed Ebert from the tether of silent misery. (When you’re in a zone, he says, all the worries get pushed back.) The brain worked fine. It could process the emotions while the fingers could capture those thoughts in the perfect voice that runs through our heads. Ebert could say what he wanted. He didn’t have to bang and gesture and hope Chaz, his saintly wife, understood him. With writing, he was nobody’s victim, no one’s charity case. He was Roger, the storyteller.

Ebert’s writing was filled with compassion and humanity. James, via interviews and his sympathetic coverage of Ebert, proves that was more than a literary device. He got that way, I think, by eating from life’s plate with both hands. His circle of friends and admirers kept growing, from Martin Scorsese to Errol Morris to Ramin Bahrani (Man Push Cart). A longtime bachelor, he was married at age 50 and got a family in the process. He hit the Internet with a vengeance, recruiting new writers along the way, in his 60s.

Roger Ebert taught me how to write. Turns out he was also teaching all of us how to live. [R]