Bruce Klauber, June 2013

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW

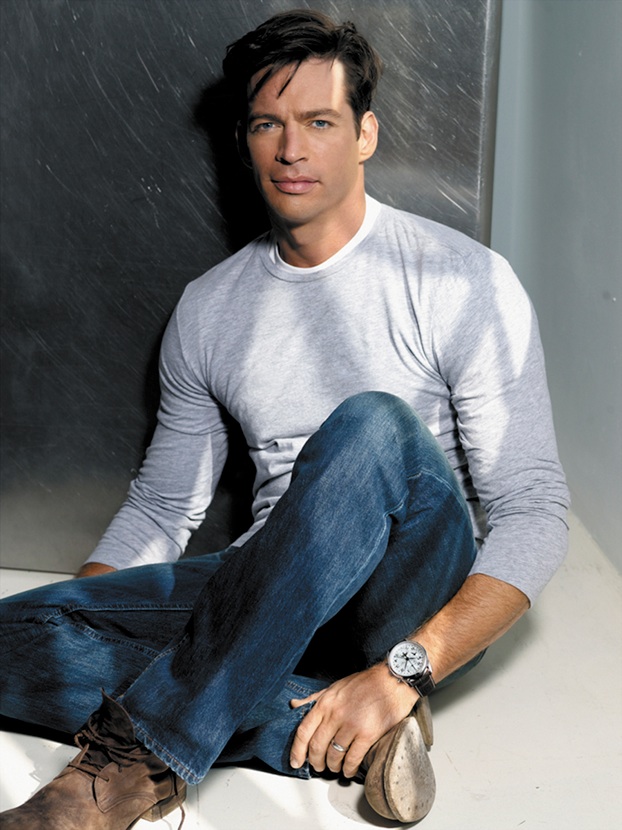

Wild About Harry

As a performer, there just isn’t much that Harry Connick Jr. hasn't done. He’s conquered almost every existing medium and has done a good deal of what he does without compromise and with integrity intact. Connick will be coming to the Kimmel Center on June 25 in support of an extraordinary new CD, Every Man Should Know.

And other than jazz drummer Gene Krupa, he is the only “matinee idol”—if there still are such things—ever produced by the world of jazz.

Since first breaking through as a jazz pianist when he signed with Columbia Records in 1988, he has reached an incredible level of fame as a concert attraction, star of Broadway, television and motion pictures; recording artist, jazz pianist, vocalist, and as used to be said, star of stage, screen and television. He has carried this considerable fame with modesty, dignity, confidence, grace, humility, sincerity, passion, good humor and a dedication to his craft and to his first love, jazz.

All of this came through during a recent and wide-ranging conversation that covered everything from “talking technical shop,” to the future of jazz, to his present, past and future in the business.

By his own admission, he is an intensely private person and consequently, to his credit, may be the first mega-star in history to not have become tabloid fodder. Until recently that is, by way of a “situation” played out on national television, on American Idol, no less, one of the most-watched television programs in the country.

For those who missed it, Connick was a “guest mentor” on the program, meaning that his role was to give advice to some of the up-and-comers. The timing of his appearance was appropriate, as in that episode, the singing competitors were asked to perform an American pop song classic. Among the songs sung were “My Funny Valentine” and “Stormy Weather.” Connick was, shall we say, a bit hard on the contestants and their “renditions,” strongly pointing out that a singer must know what the song is about before it is sung. The guest mentor made it quite clear that, from what he heard, it was obvious they had no idea.

The next day, the national jazz community went wild on social media, saying in part that it was about time someone said this. And that Harry Connick Jr. was the man to say it.

“I didn’t plan on saying what I said,” he remembers, “and I had no idea the jazz community was so happy about what I said. What I did hear was that I got in a fight with [judge] Randy Jackson, and I think that’s hysterical. First, it wasn’t a fight. Talking like this stimulates people and that’s what we love to do: talk about music. The last I checked, that show is about music. I like Randy Jackson. I’ve known him for years. I just disagreed with him. With the whole mentoring thing, what I believe is that there are a couple of ways to learn how to play. You listen to records, you go out on gigs, and whenever you have an opportunity to learn from the older cats, you do. In this case, I was the older cat and was teaching them what I thought would help them. But what they didn’t show was the half-hour that I spent with each of them, when I said, ‘Take this stuff with a grain of salt. This is what I think, but you all have to do what you have to do. Which I think they all ended up doing anyway.

“Right after I did that, I called my mentor and teacher Ellis Marsalis on the phone and said ‘thanks.’ I’d be playing a tune in his class, and he would ask, ‘What are the lyrics?’ I’d be playing it, and not singing it, but he still wanted me to know what the lyrics were. He would say, ‘What’s the tune about?’ I would say, ‘I don’t know’ and then he would say, ‘Well, then you can’t play it. You need to learn the lyrics. You need to know what you’re playing about. And that goes for the verses, too.’ He was brutal with us. That’s how you learn.

“What you also didn’t see on the air was that I was trying to explain to them that you can’t sing ‘runs’ unless you know harmonically what you’re ‘running’ over. So a lot of these young women just didn’t know harmony. I wasn’t trying to squelch their individuality, but you can’t do what they were doing unless they knew exactly what chords were going on underneath them. But it was fun and I had a good time. No, we haven’t talked about me coming back, but I’d do it—mentoring—on TV or off TV.”

And of today’s crop of Connick wannabes?

“You know, I really don’t listen,” he says. “If there were a clone of me, I would be so happy, but that would mean they would have to do what I do. And I haven’t seen anybody do that yet. I’ve seen people singing tunes, but I haven’t seen those people doing the orchestrations and conducting. I haven’t seen anybody present the music the way I present it. Not that I’m better than anyone else. Just because somebody sings a standard doesn’t mean I’m going to stop in my tracks and check it out. This isn’t a slight to any of the people out there. I honestly just don’t listen.”

“Passion” is one thing that comes through when speaking with him, and for him, this passion for music began in his native New Orleans when he first started taking piano lessons at the age of three. Two years later, he made his first public appearance and five years after that made his first jazz record. He fell under the spell of the elder Marsalis when he attended the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. What has happened in his career—helped in no small measure to his marvelous soundtrack to the 1989 film, When Harry Met Sally—is unparalleled in show business history. When and if a history book about such things is written, it will say that only Mel Torme almost came close to Connick’s utter completeness.

Now 46, he is again tackling new territory—and a sensitive territory it is, with the making of his new CD, Every Man Should Know. This stands as the first album of all-original Connick songs, and the first ever he has written that tell of the real man, his emotions and his vulnerabilities. And he does it with a stellar group of songs that explore almost every style of music there is, including jazz, Latin, country, gospel and funk. It is impossible not to hear how deeply he is feeling about what he is singing. If Sinatra wrote songs, they might have sounded like a few of these.

Why is he opening up now? At this point in the interview Connick took a rather personal and introspective detour:

This is the first time you’ve let your inhibitions down and allowed the vulnerability to show and share personal experiences. Let me tell you, it really comes across.

“Wow, thank you. That means so much, man.”

What possessed you to do this now?

“Like when I go in the studio—you ever see those photographs of Frank Sinatra in the studio and all these celebrities are there—I never did that. I don’t feel comfortable with a bunch of people standing around. It’s so focused...when I’ve written the orchestrations and arrangements and I go to conduct, I have to focus. I don’t want to be distracted. I don’t want cameras in there, I don’t want people in there; so I go in the studio and I mix it and there’s nobody there. It’s just me and my friend Tracy and the engineer.

“I’ve been in this bubble and my wife tells me all the time, ‘Why don’t you ever let people in? Like nobody knows what you do.’ I said, ‘Because that doesn’t matter,’ and she said, ‘No it does matter. Harry, I’m frustrated because I know what you can do, but nobody gets to see it.’ My record company said I should open a Twitter account, something I have no interest in. And I asked my wife, ‘What do you think?’ and she said, ‘Yeah, let people into your life a little bit.’ So, today—so weird that we’re talking today—I posted a video of myself in the studio— today!—and my wife said, ‘You need to do more of that, let people into your world.’”

You got a nice lady there.

“Oh, she’s great, man. And I realized how can people know what I’m doing if I don’t let them into the process. I’ve always made up stories with my songwriting—I found it to be more fertile ground because there were no limits on what I could make up. But on this record, when you deal with personal experiences, it has a tendency to pull the boundaries way in. I started from that point with the lyrics and then sometimes they stayed right in the wheelhouse, but on the third track called ‘I Love Her,’ a bossa nova tune—that’s just straight up about my wife. And then there’s another song called ‘Come See About Me,’ which is me thinking about what it would be like not to have my wife. I never wanted to let anyone in my life before.”

How does it feel? Does it take a load off?

“I don’t know, man. Again, it’s been a very personal process. Like on that one song, ‘Come See About Me,’ I started to cry because, you know, something clicked in my head when I was singing the lyrics, which is something you want to do...and I looked over at my buddy Tracy and he’s like, ‘Man, maybe you should do it again,’ because, you know, there’s nothing more heartbreaking than watching someone try not to cry. So I did it again and I really struggled and I’m wondering, man, when I go on the road—as an actor, when you’re singing someone else’s lyrics or something that doesn’t apply to you, you can get very close to those emotions. But when they’re your personal experiences...I don’t know how I’m going to get through some of these tunes.”

In ‘Come See About Me,’ isn’t there something about I’ll pay your cab fare and letting the meter run?

“Yeah, how pathetic. The first line of the tune is ‘I don’t want to bother you’ and the next line he says, ‘But can you come over’”

I’m sure you’ll feel it, the intensity, but as time goes on...

“Yeah, you’d think so. But I’m just wondering how I’ll get through the first ten times. I was talking with Branford [Marsalis] the other day and I asked him, ‘You ever cry when you play?’ He said, ‘Yeah,’ and I asked, ‘Is it hard?’ And he said there’s a technique to it—’I’ve cried when I’m playing and I’ve learned how to develop that sound and use it when I want to use it if I can’t access those emotions.’ When you’re singing, though, it’s almost impossible. When you’re playing the piano you can cry all you want. He said, ‘Why do you ask?’ and I said, ‘Man, some of these

songs hurt.’ I think as you get older you realize life’s too short and you start letting

the silly stuff go and you cut down to the common denominator of who you are—and that’s pretty scary, because you start cryin’ about stuff.”

I’m hearing things in your voice—there’s emotion here, it’s heavy. They’re beautifully written tunes, but it’s how you sound on them, which is what you’re saying to me.

“I really want to go in the studio and do a record that’s all ballads, kind of under the umbrella of [Frank Sinatra’s album] Only the Lonely. It’s just ballad after ballad of, you know, sad songs. I would like to see how I’d sound on that, because I’m definitely able to access different emotions now. Sometimes if you start letting that stuff go, other kinds of performances come out.”

I’m just curious—was there ever a time when you were a musical snob? I mean, today if it ain’t “Night in Tunisia,” forget about it.

“Oh, man, I’m so glad you asked about that. That’s another thing that Branford and I were talking about. We all were under the Winton spell, and I don’t think even Winton’s under the Winton spell anymore. If it wasn’t clean, it was blasphemy. I would have never put a tune like the first one [‘What Every Man Should Know’] on this record. I mean, there’s no way. I would never have even used an electric bass. I still have a problem with keyboards. But those were the years that it was about honing my craft. I couldn’t hone my craft unless I spent all my waking hours working on it. What I didn’t realize in that snob phase was I forgot about my history. When I was 18 I got signed to do a jazz record and I stopped playing classical, stopped playing rock. And then a few years down the road I made a couple of New Orleans funk records and then people looked at me as though I was from Mars. And that was about the time that I said, screw it, you know, who am I answering to? I know the rules, I know how to play, why can’t I play what I want to play? So this record is a testament to that. The tunes kind of wrote themselves. It’s like the old Michaelangelo story when they asked him how he carved the horse out of a block of marble, he said ‘I just chipped away everything that wasn’t a horse.’”

The only critical barbs he’s endured through the years, however mild they were, came from that group of self-righteous musical purists who were not thrilled about his forays into funk or anything else that didn’t have to do with jazz.

“Hey, I was playing with the funk band, The Meters, when I was growing up, and was playing rock and roll gigs. But when I got to New York and signed with Columbia, I stopped doing everything but jazz. So this new project is a testament to that.”

He is still unsure about the exact program that will be performed on his extensive tour, which kicks off in mid-June and runs through August.

“I don’t know exactly what we’ll be playing yet, but I can promise to Philadelphians that they will never see a more enthusiastic performer,” he says. “I am so excited to play. The band I have is just off the chain. We’ll be playing stuff from the new record, old tunes, and in the last two weeks, I’ve probably written 15 charts for songs that I’ve never recorded.”

As for the future? He’s open to anything, including writing something he describes as a “long form, symphonic, big band hybrid.” And for those who need to know such things, he will not be conducting a Pops orchestra, Philly or otherwise, though he is a friend and admirer of Peter Nero “It just wouldn’t do much for me,” he says. “I spend so much time conducting my own stuff.”

“No rules, no limits,” is how Connick describes the songs on his new CD. Though the “no rules, no limits” line certainly applies to this touching and heartfelt group of new compositions, it also applies to the artist, to the man and his music. Indeed, there was a song once sung by one of Connick’s influences, that may sum up the life and art of Harry Connick, Jr. best. The name of the song is “My Way.”

P.O. Box 120 • New Hope, PA 18938 • Voice 800.354.8776 • Fax 215.862.9845 • www.icondv.com • www.facebook.com/icondv

Bruce Klauber is a published author/biographer, producer of DVDs for Warner Bros., CD producer for Fresh Sound Records, and a working jazz drummer. He graduated from Temple University and holds an Honorary Doctorate from Combs College of Music.