Bob Perkins, July 2014

Bob Perkins is a writer and host of an all-jazz radio program that airs on WRTI-FM 90.1 Mon-Thurs. 6 to 9pm & Sun., 9am–1pm.

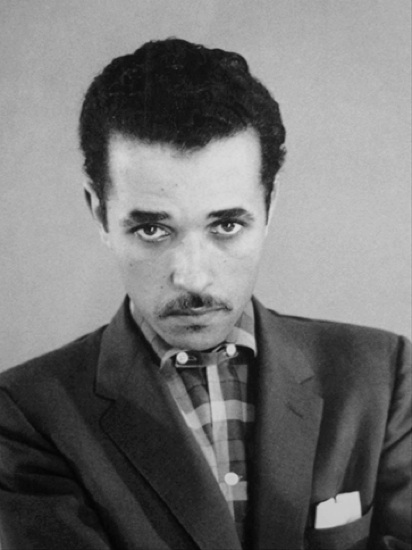

Hampton Hawes

One can go bonkers trying to figure out why a certain person or certain something, isn’t more widely recognized, even though the certain something, or person in question, are clearly worthy. Many people involved in the arts have suffered from society’s blindness, deafness, or indifference. Over the years, this has been true with jazz as a whole, and with a good number of its practitioners. One such practitioner was Hampton Hawes, who began his career as a child prodigy, and blossomed into one of the genre’s finest and most inventive pianists.

Hawes entered the world November 12, 1928 in Los Angeles, California, and found out about the piano through his mother, who played piano in Westminster Presbyterian Church, where her husband was pastor. While a toddler, Hawes would sit on his mother’s lap while she practiced. He was soon able to able to tap out complex tunes by the time he was three. From then on he was mainly self taught, and in his teens was making music with some of the well known jazz figures on the West Coast—Dexter Gordon, Art Pepper, Wardell Grey and Shorty Rogers, to name a few.

What really put him on cloud nine at age 19, was playing for eight months in a group headed by trumpeter Howard McGee that included Charlie Parker.

Hawes served in the army from 1952-1954, and upon his release formed his own trio. Following a national tour of Europe in 1956, Hawes won the “New Star of the Year” award in Down Beat magazine, and “Arrival of the Year” honors in Metronome.

Hawes sabotaged his career to some degree by becoming addicted to heroin, which prompted a federal undercover probe of drug trafficking in Los Angeles. Hawes was targeted and asked to inform on suppliers in exchange for some leniency. He refused to cooperate, and on his 30th birthday was sentenced to ten years in a federal prison hospital.

He applied for a pardon in 1961 from President John Kennedy, and by a great stroke of good fortune, he, along with several dozen other prison inmates, were granted executive clemency in the final year of JFK’s presidency.

His spirits buoyed by his release, Hawes resumed playing and recording, and during a world tour in 1967 discovered he’d become a big name abroad. During almost a year touring Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, Hawes recorded nine albums and played to sold-out club and concert venues in ten countries.

Hawes became an author and, in his autobiography Raise Up Off Me, focused on his heroin addiction and the so-called bebop movement, of which he was a part. The book won high praise from a number of well-known jazz critics and writers, and was awarded the prestigious Deems Taylor Award for music writing in 1975. The Penguin Guide to Jazz, also heralds the book as “one of the most moving memoirs ever written by a jazz musician…“

If one knows something about jazz and, in particular, excellent jazz piano execution, they would be able to identify the playing of Hampton Hawes immediately. His gospel leanings are evident. His dad being a minister and his mom a church pianist, shine through. But he also did so many other interesting things, and his blends were, in great part, pleasing. I play his music often on the air. Every now and then, a listener with finely-tuned ears will call and ask, “Isn’t that Hampton Hawes? Wow! He was marvelous.” And I know I’ve not just been hearing things when Hawes plays. But somehow, he was just another highly-prized (to some) jazz artist, who wasn’t identified on the home front’s radar.

Hampton Hawes died of a brain hemorrhage in 1977 at the age of 47. The City Council of Los Angeles passed a resolution declaring November 13th (Hawes’ birthday) Hampton Hawes Day throughout the city in perpetuity

The Green Leaves of Summer, is one of his best albums. The title track alone is worth the price.